New books are a certain sign of autumn and this year is no exception. Among the books I look most forward to this autumn is Självständig prinsessa – Sophia Albertina, 1753-1829 by my fellow historian Carin Bergström, who is head of the Swedish Royal Collections. Princess Sophia Albertina of Sweden and of Norway was the only sister of King Gustaf III and King Carl XIII and became secular abbess of the Protestant convent of Quedlinburg, which she lost in the Napoleonic Wars. She is also remembered for having built the Hereditary Prince’s Mansion in Stockholm, which is now the seat of the Foreign Ministry. Surviving well into the reign of Carl XIV Johan, she also became an important symbolic link between the old Holstein-Gottorp dynasty and the new House of Bernadotte. The book will be published by Atlantis in October.

New books are a certain sign of autumn and this year is no exception. Among the books I look most forward to this autumn is Självständig prinsessa – Sophia Albertina, 1753-1829 by my fellow historian Carin Bergström, who is head of the Swedish Royal Collections. Princess Sophia Albertina of Sweden and of Norway was the only sister of King Gustaf III and King Carl XIII and became secular abbess of the Protestant convent of Quedlinburg, which she lost in the Napoleonic Wars. She is also remembered for having built the Hereditary Prince’s Mansion in Stockholm, which is now the seat of the Foreign Ministry. Surviving well into the reign of Carl XIV Johan, she also became an important symbolic link between the old Holstein-Gottorp dynasty and the new House of Bernadotte. The book will be published by Atlantis in October.Another book I look forward to is The Diamond Queen: Elizabeth II and Her People by the well-known BBC journalist Andrew Marr, which is also expected in October. Ahead of Queen Elizabeth II’s diamond jubilee the journalist Robert Hardman has also written Our Queen, which is just out and for which he has been granted exclusive interviews by family members and others close to the British monarch.

Margrethe II is another queen who will celebrate a jubilee next year and the art historian Thyge Christian Fønss has written Portrætter af en dronning – Dronning Margrethe den II i portrætkunsten 1972-2012 (yes, the grammatical mistake seems to be on the cover), which examines the painted portraits of the Queen of Denmark. The book is expected to be published in two weeks. A related book is The Queen: Art & Image, which deals with the iconography of Elizabeth II and is related to a travelling exhibition by the National Portrait Gallery of her portraits leading up to the diamond jubilee.

In Norway we can look forward to the fifth volume of Tor Bomann-Larsen’s biography of King Haakon VII and Queen Maud, Æresordet, which will be published by Cappelen Damm in November. This fat volume will take the story from after the formation of the first Labour government in 1928 to the black day of 7 June 1940, when the King had to leave his country. The sixth and final volume is expected in 2013. Ingar Sletten Kolloen’s authorised biography of the Queen, which was also expected this autumn, has been postponed to the autumn of 2012, I have been told.

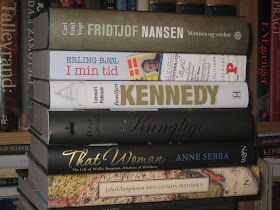

In politics we can expect the journalist Thor Viksveen’s biography of the Prime Minister, Jens Stoltenberg – Mannen og makten, to be published by Pax in November. The book has obviously had to be altered and updated quite a lot in its final stages, given the events of this summer and the PM’s much-praised handling of the situation. Another Norwegian Prime Minister, Ole Richter, best remembered for his suicide in 1888, is the subject of Karl Over-Rein’s biography Ole Richter - Statsministeren som valgte revolveren.

Christopher Hitchens has collected some of his essays and articles in a monumental volume titled Arguably. Another collection of essays and articles out this autumn is I min tid – Artikler og tilbageblik 1938-2011, which collects some of the now 93-year-old Danish journalist and political scientist Erling Bjøl’s articles from 1938 to 2011. Bjøl’s classic history of the USA, which he keeps updating despite his age and blindness, will also be published in a new edition this year and also in a Norwegian translation.

In Denmark we can also expect the prolific Henning Dehn-Nielsen’s Danmarks konger og regenter, to be published by Frydendal in November, which seems to be another encyclopaedia-like book on all the Danish monarchs. Apparently there is also a book out about Queen Caroline Amalie, Den gode dronning i Lyngby - Historien om dronning Caroline Amalie og hendes socialkulturelle base by Arne Ipsen, but I have not been able to find any more information about that.

This year marks 150 years since the birth of the explorer and statesman Fridtjof Nansen, which has so resulted in two biographies. Carl Emil Vogt has written Fridtjof Nansen – Mannen og verden, while Harald Dag Jølle has just released the first of his two volumes, Nansen – Oppdageren. Among the other Norwegian biographies out this autumn is Per Eivind Hem about Paal Berg, the leader of the home front during WWII, who was given the task of forming a national coalition government in the summer of 1945 (but failed) and eventually became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Fifty years after the inauguration of John F. Kennedy as US President his family continues to fascinate and Historiska Media in Lund has just published the journalist Lennart Pehrson’s book Familjen Kennedy, which I have just read and found quite good. Another Swedish book on my reading list is John Chrispinsson’s Den glömda historien – Om svenska öden och äventyr i öster under tusen år, which deals with the history of Sweden’s lost eastern provinces.

Among the new history books is also Jean-Vincent Blanchard’s biography of Richelieu, titled Éminence: Cardinal Richelieu and the Rise of France and published by Walker & Company.

On the subject of royalty there will not be many books in Sweden this year, which is quite understandable given the unusually high number of such books published last year (which saw the Crown Princess’s wedding and the bicentenary of the dynasty), but the British journalist Peter Conradi’s excellent book on the current European monarchies has just been published in a Swedish translation by Forum with the title Kungligt – Europas kungahus – Släktbanden, makten och hemligheterna.

The author Helen Rappaport, who has written several books on Russian history, has now shifted the focus westwards and November will see the publication of her book on the death of Prince Albert of Britain and its impact, titled Magnificent Obsession: Victoria, Albert and the Death that Changed the Monarchy.

December will see the 75th anniversary of the abdication of King Edward VIII of Britain and Anne Sebba marks the occasion with That Woman: The Life of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, which was published a month ago.

For those interested in historical novels I can mention that Karsten Alnæs has written I grevens tid, which deals with the early life of Count Herman of Wedel-Jarlsberg, one of the most significant Norwegian politicians of the early nineteenth century, and that Gyldendal will soon publish Cecilie Enger’s Kammerpiken, which tells the story of Hilda Cooper, the young British woman who came to Norway as Queen Maud’s dresser and continued to live at the Palace in Oslo until just before her death in 1992.